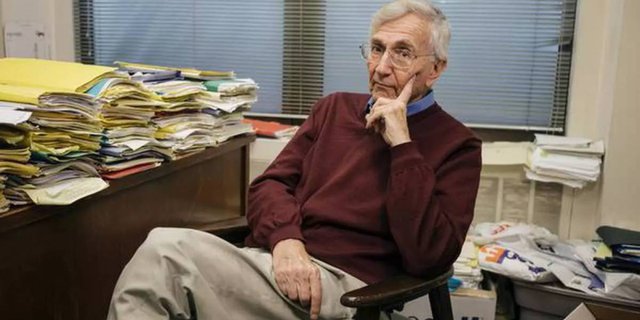

Dream – Seymour Hersh is no longer young. This legendary investigative journalist was recently criticized for reporting on the sabotage of Russia's Nord Stream pipeline by the United States.

The Pulitzer Prize winner wrote a recent article stating that America was responsible for the explosion of Nord Stream, an underwater gas pipeline connecting Russia and Germany.

“The direct source” of the sabotage is an unwitting and anonymous protagonist from the controversial recent article by journalist Seymour Hersh about the alleged US involvement in the explosion of three out of four Nord Stream gas pipelines on September 26, 2022, published on February 8, 2023, on his personal blog at https://seymourhersh.substack.com titled “How America Took Out The Nord Stream Pipeline” or “How America Destroyed the Nord Stream Pipeline.”

(Explosion of the Russian Nord Stream gas pipeline due to sabotage/BBC)

Hersh claims that the C4 explosive was planted in June 2022 by US divers during NATO exercises in the Baltic Sea, and it was detonated three months later by the Norwegian Navy.

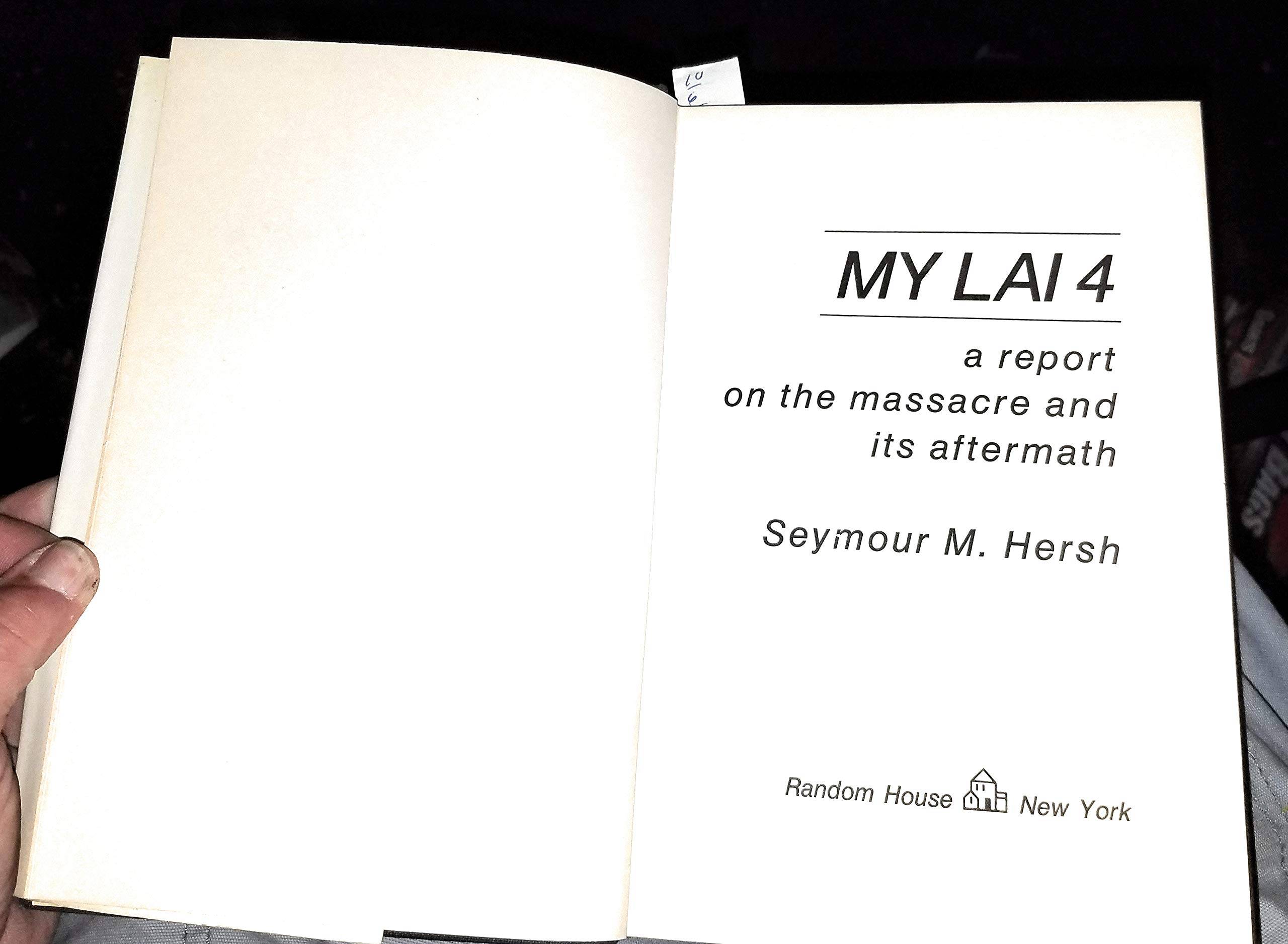

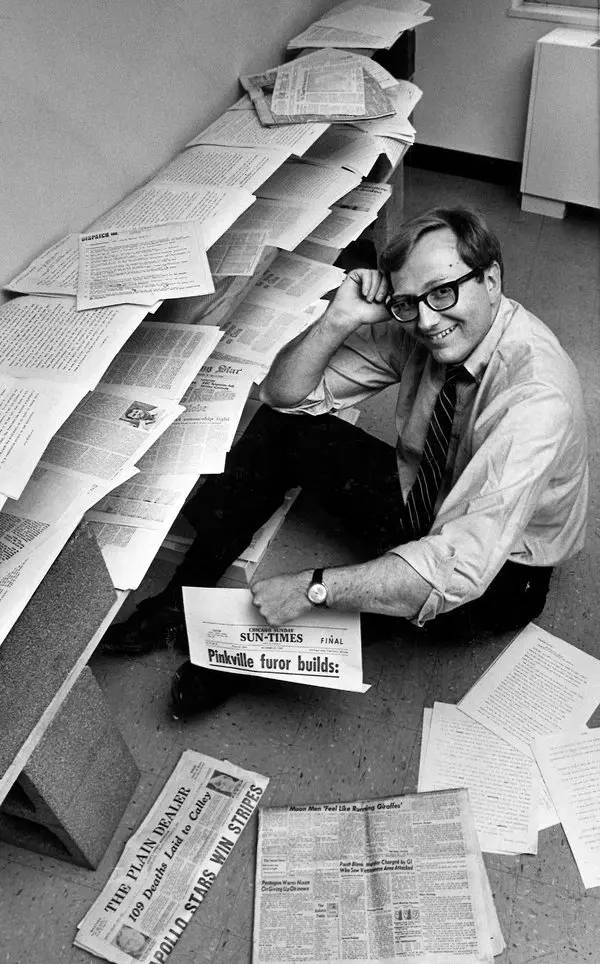

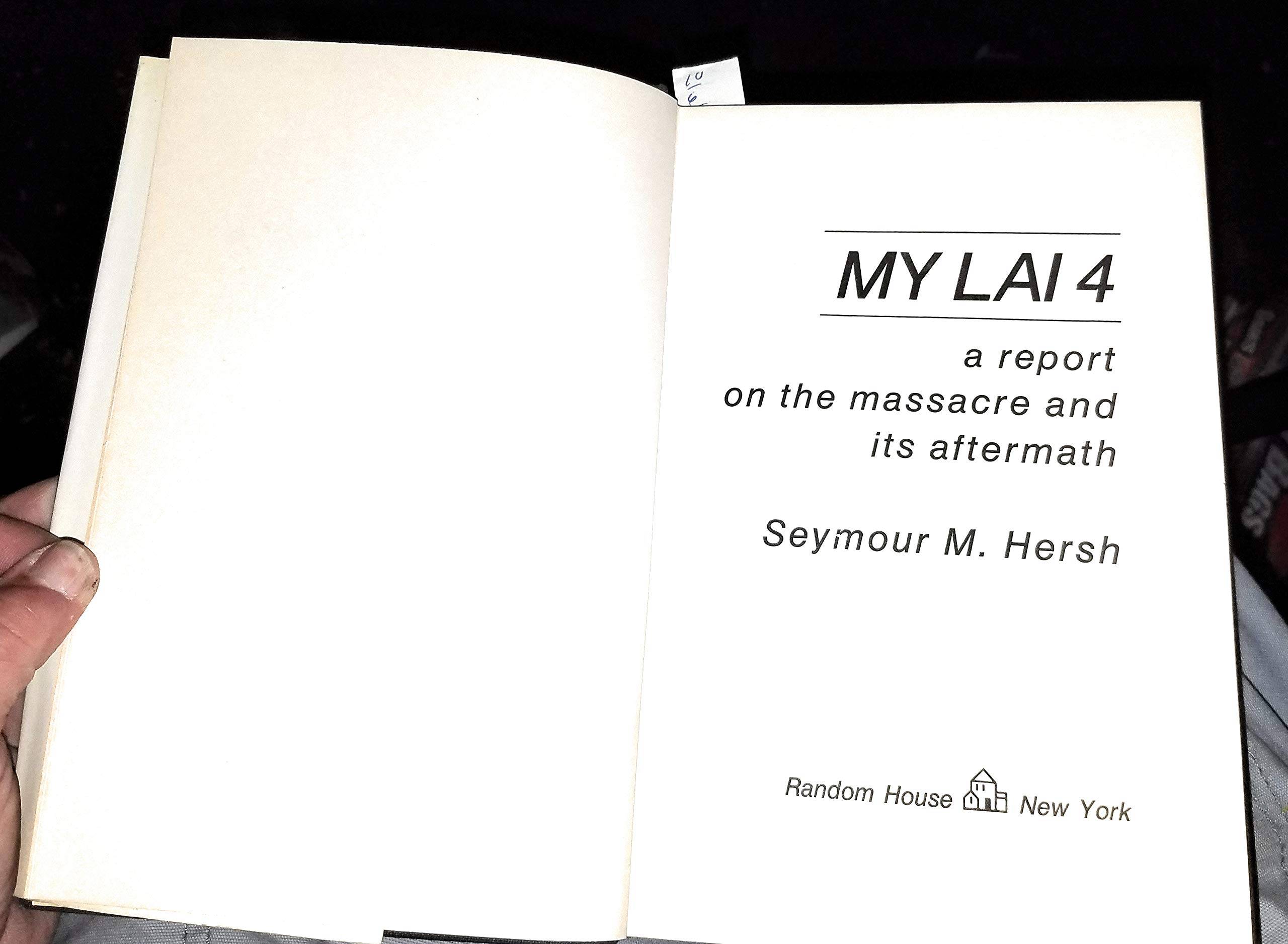

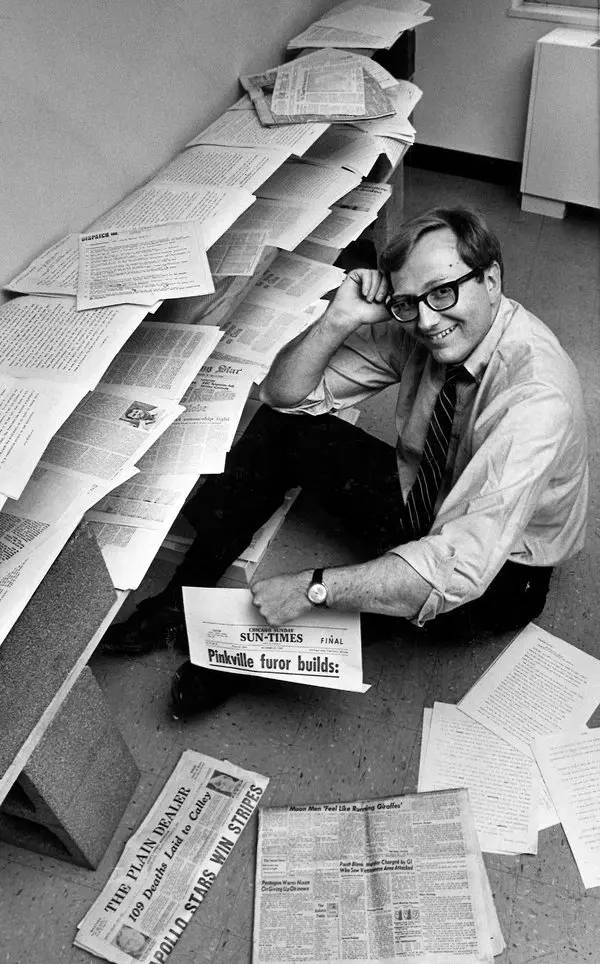

Hersh, the Pulitzer Prize winner in 1970 for exposing the My Lai massacre during the Vietnam War, relies on a single source for the report, which some people consider a conspiracy theory. The controversy has sparked an information war in the news media.

(Hersh's report on the My Lai massacre in Vietnam by US troops/JFKU)

The White House denies Hersh's allegations that the US was behind the sabotage: "It is completely false fiction."

But Hersh argues that the pipeline represents a “cheap Russian natural gas political threat” to Germany and Western Europe, as well as competition for US gas exports. For the most critical readers, Hersh's story lies between disinformation and truth.

The veteran investigative journalist, the son of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, made these allegations in early February 2023 on his website.

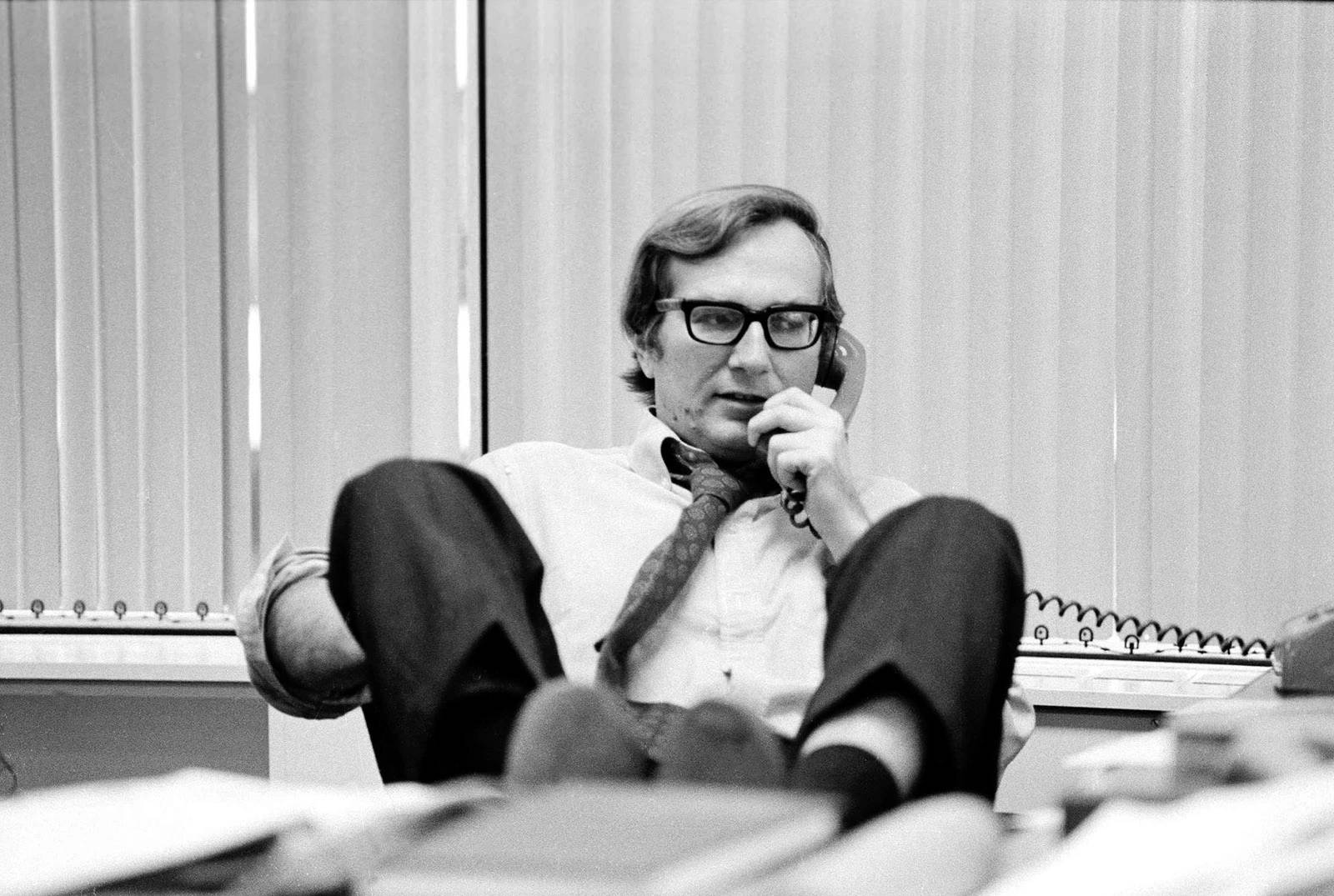

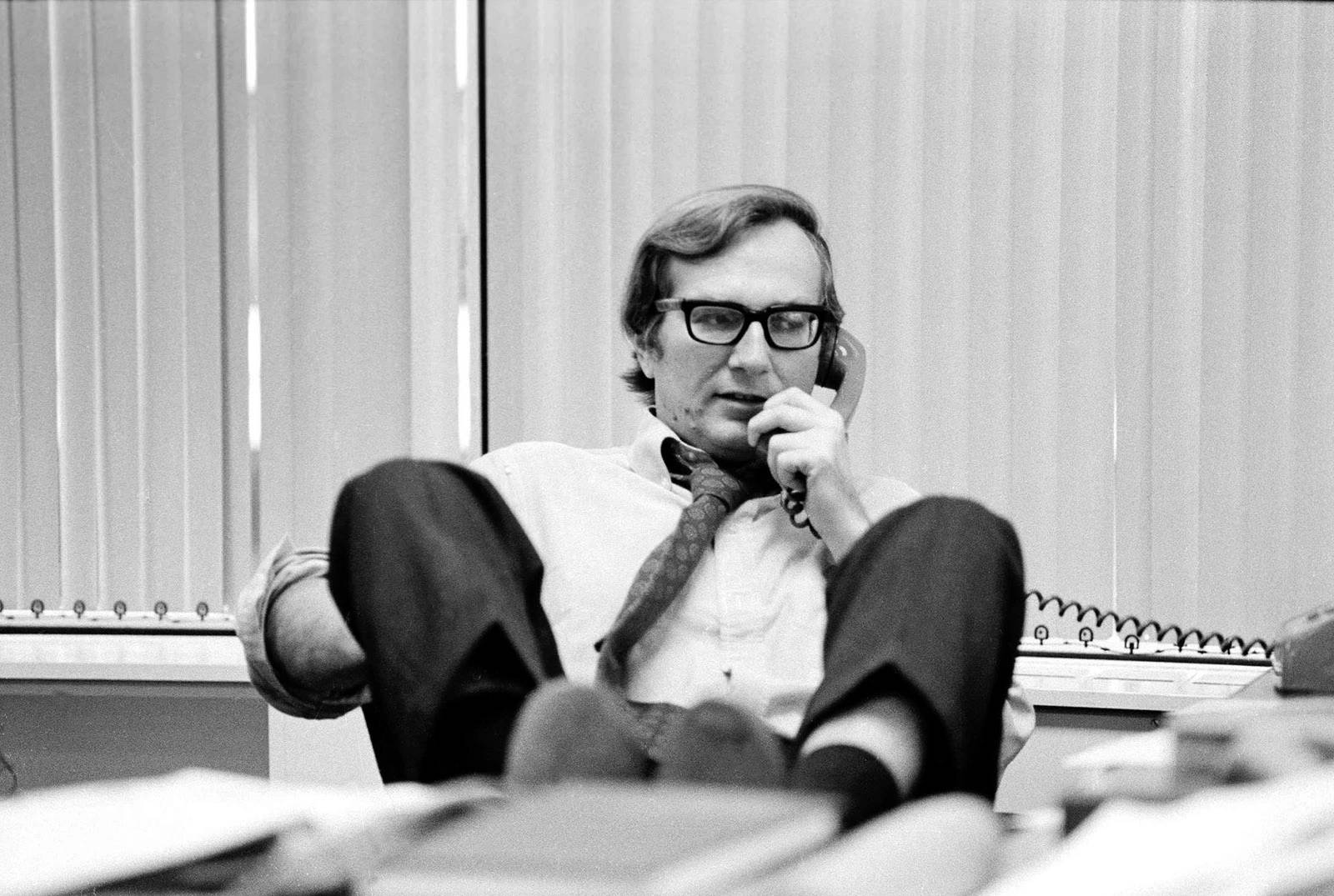

Hersh has worked for prestigious publications such as The New York Times, the newspaper that covered the Watergate scandal in the 1970s.

(Hersh working at The New York Times/NYT)

He also broke the story of the 2004 investigation into torture at the CIA's secret prison in Abu Ghraib (Iraq) for The New Yorker magazine, and no one disputed a word of the news he wrote.

(Torture of Abu Ghraib detainees by US troops/WG)

The Nord Stream explosion report is not Seymour Hersh's first controversial report. In 2013, he refuted Western government accusations that President Bashar al-Assad of Syria ordered a chemical weapons attack in Ghouta, a suburb of Damascus. Hersh instead blamed Syrian rebels. “I wrote a story full of reasons why (the Syrian Army) might not be responsible (for the attack), but the story wasn't picked up in the US,” Hersh said in a 2019 interview with El Pais.

Two years later, he wrote in the London Review of Books that the US and Pakistan had lied about the circumstances leading to the death of Osama Bin Laden. The use of anonymous sources by Hersh in the report raised suspicions and marked a turning point in his career–he became an outsider. No longer an objective and impartial reporter, Hersh began taking sides. Those two important articles–the Syrian chemical attack and Bin Laden's death–were rejected by The New Yorker magazine, known for its meticulous fact-checking.

Challenging official statements with credible information from anonymous sources, especially in sensitive cases, has long been one of Hersh's main investigative techniques.

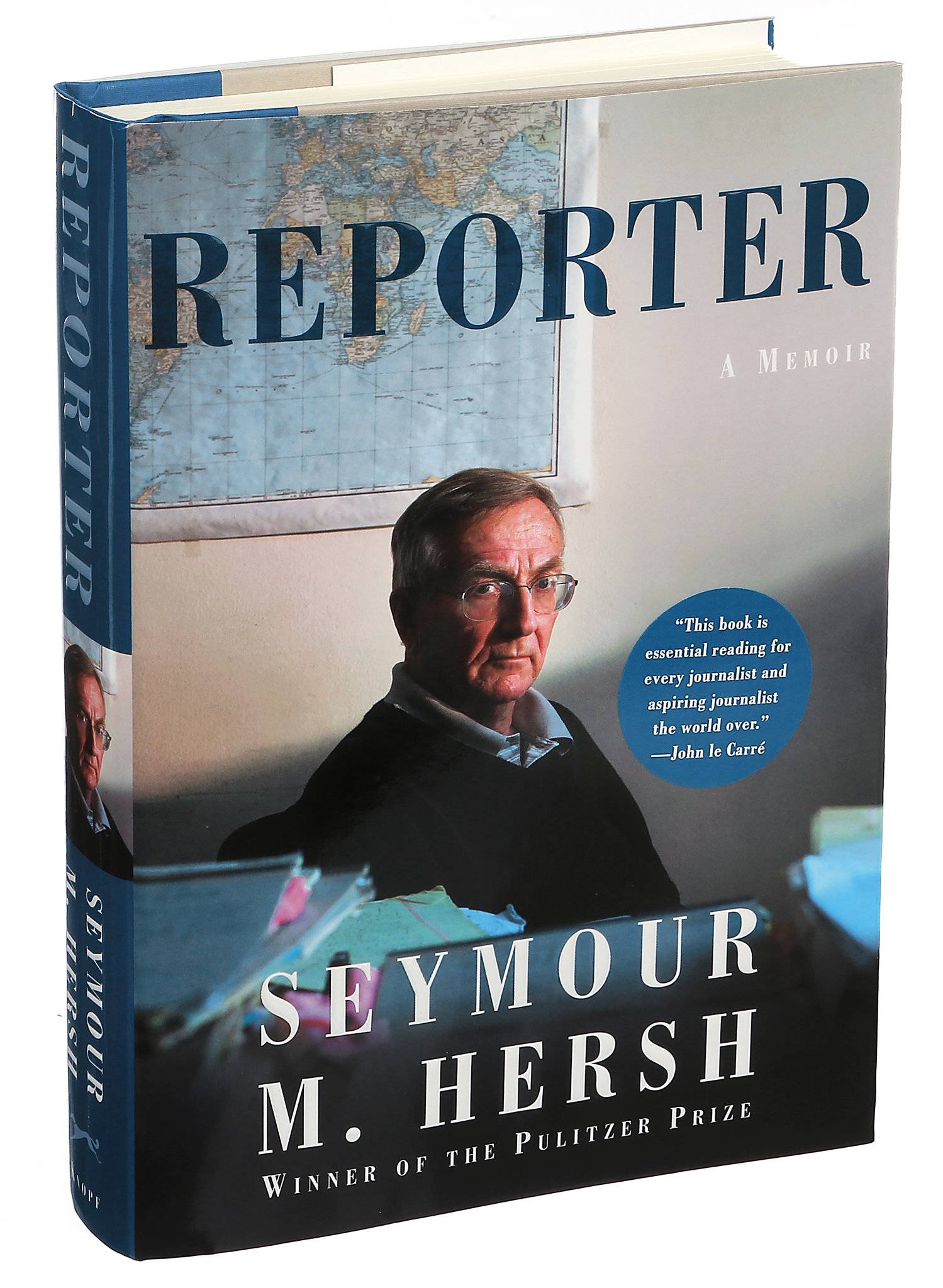

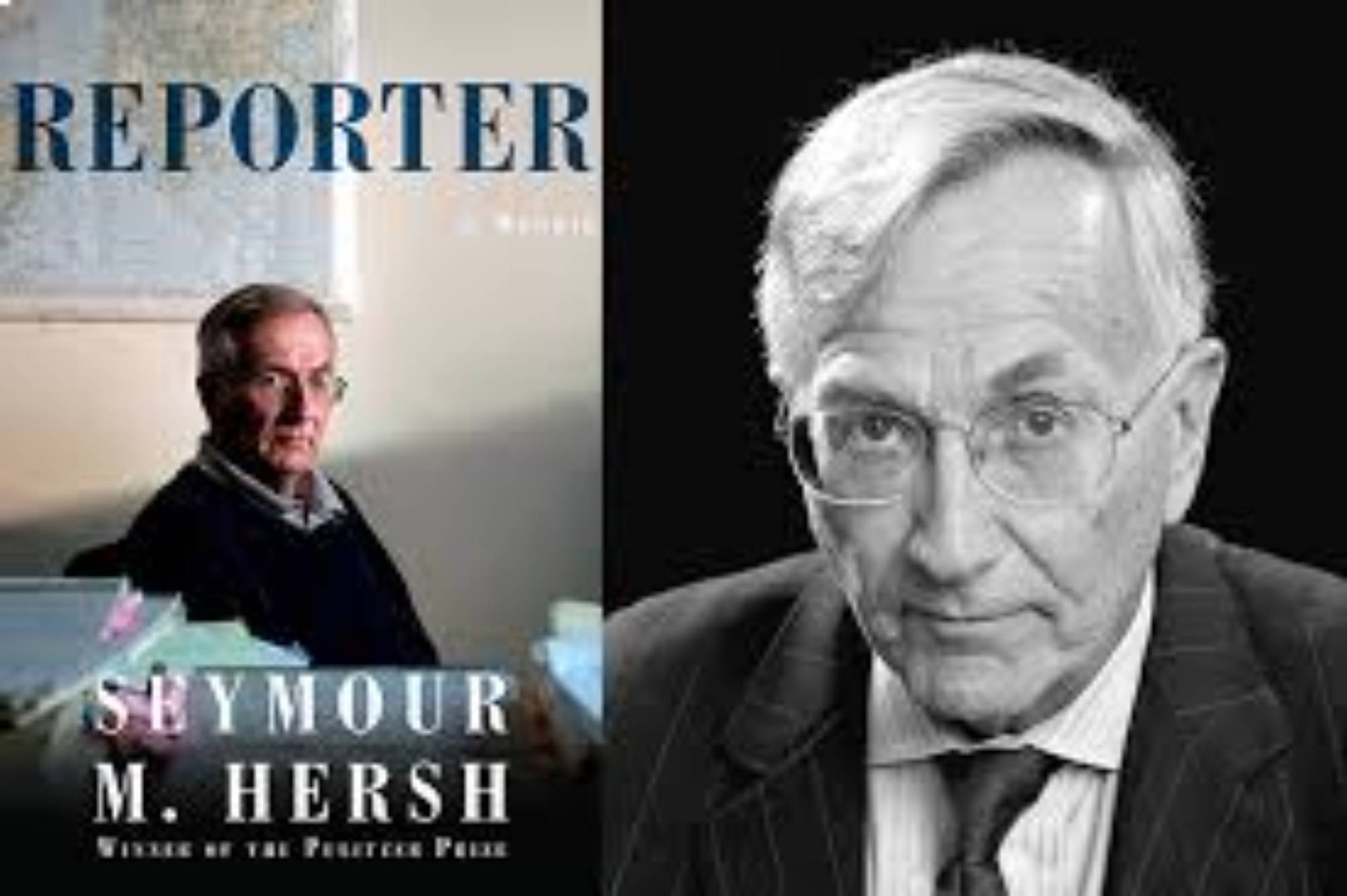

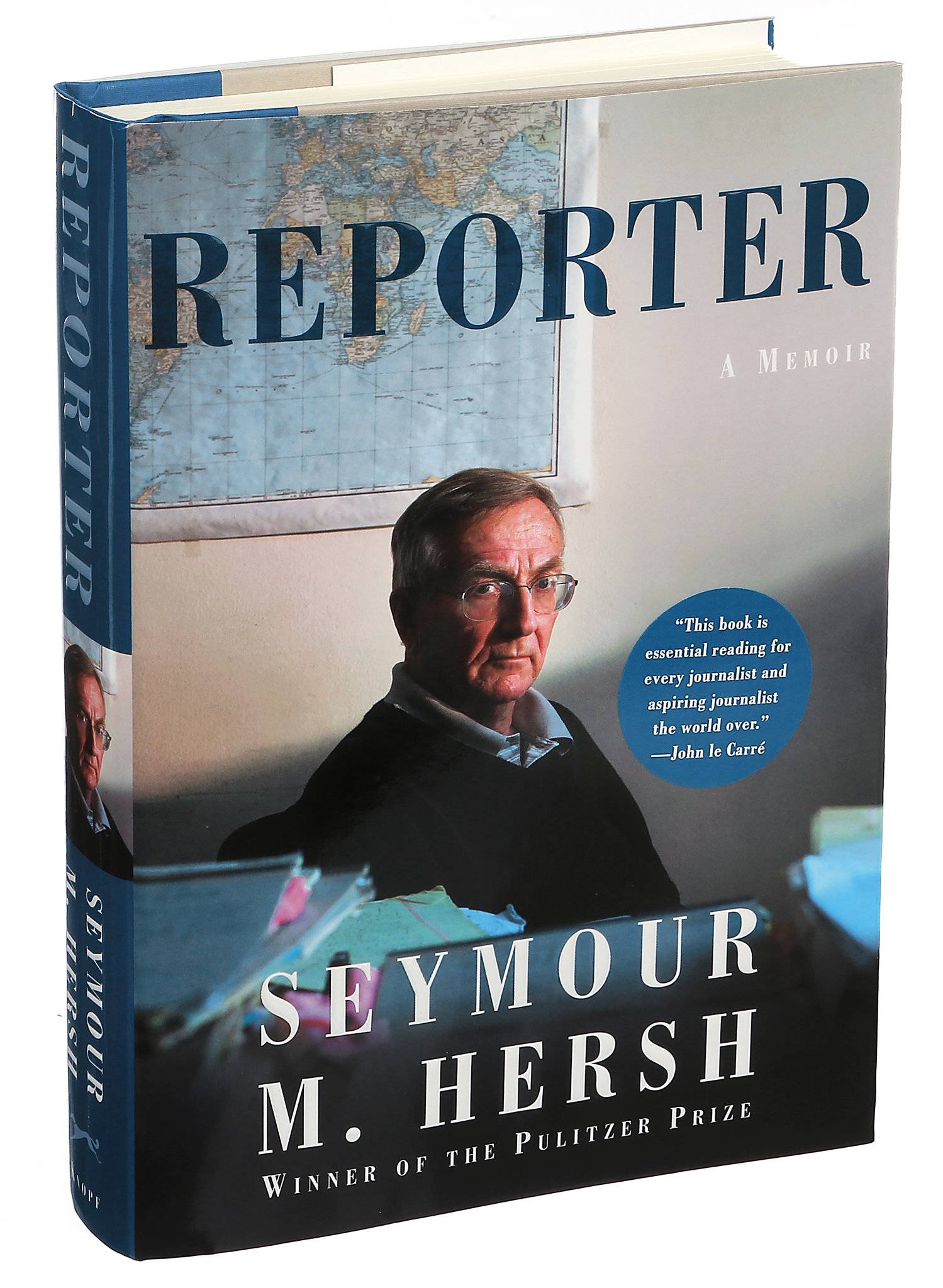

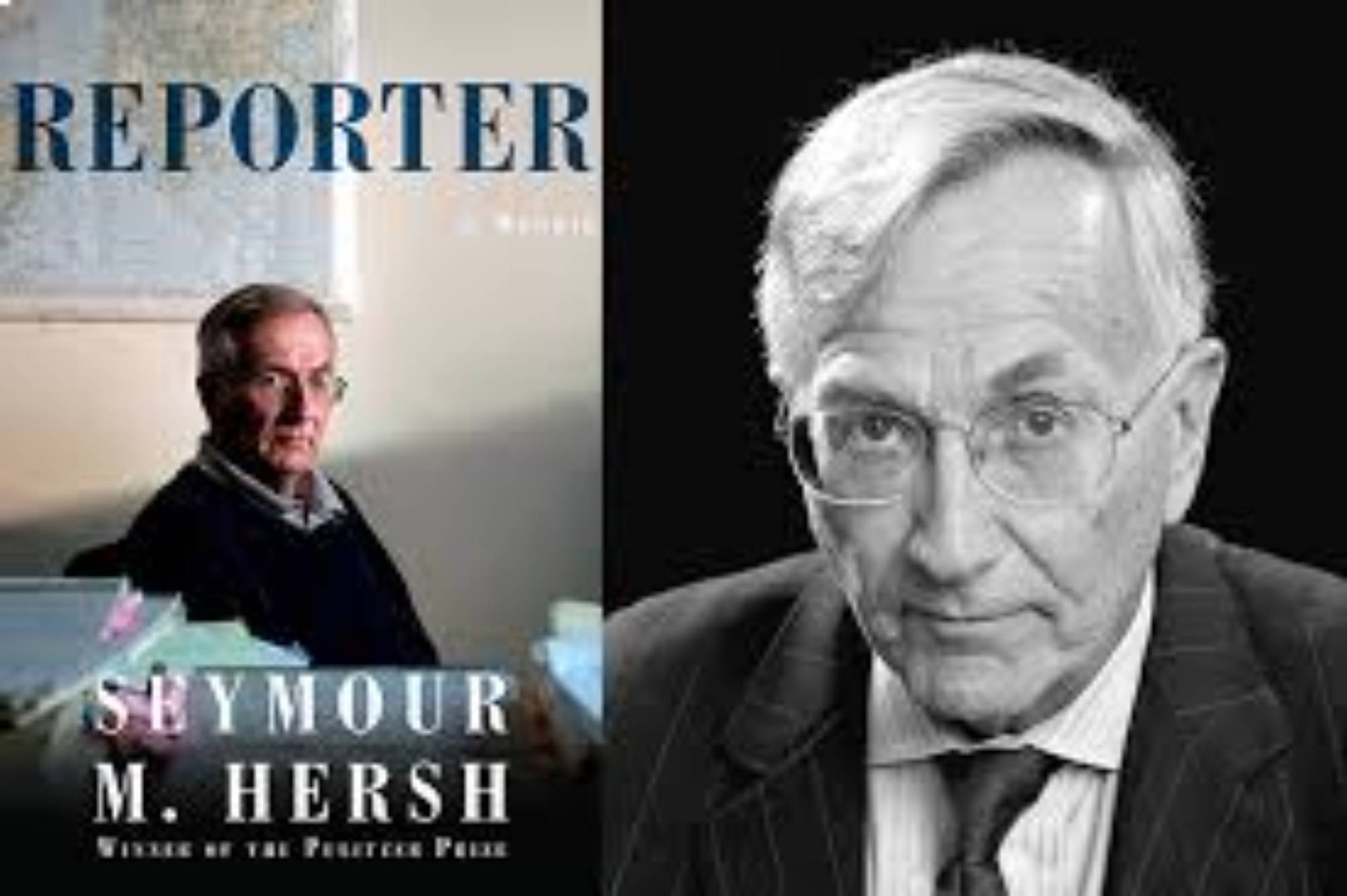

While many now consider this line blurred disinformation, Hersh does not budge an inch. “I am happy to let history judge my recent work,” he wrote in his book: “Reporter: A Memoir” (2018).

(Seymour Hersh's book: “Reporter: A Memoir” (2018)./New York Times)

In his memoir, Hersh writes about his childhood working in his family's laundry business. He attributes his curiosity to his immigrant parents from Eastern Europe. He describes himself in Reporter as a "survivor of the golden age of journalism." It was a time when "we didn't have to compete with 24-hour news channels, newspapers were flooded with advertising revenue, and I was free to travel as much as I wanted," he said. Journalists could focus on uncovering “important and uncomfortable truths,” said Hersh, who takes pride in doing so for 60 years.

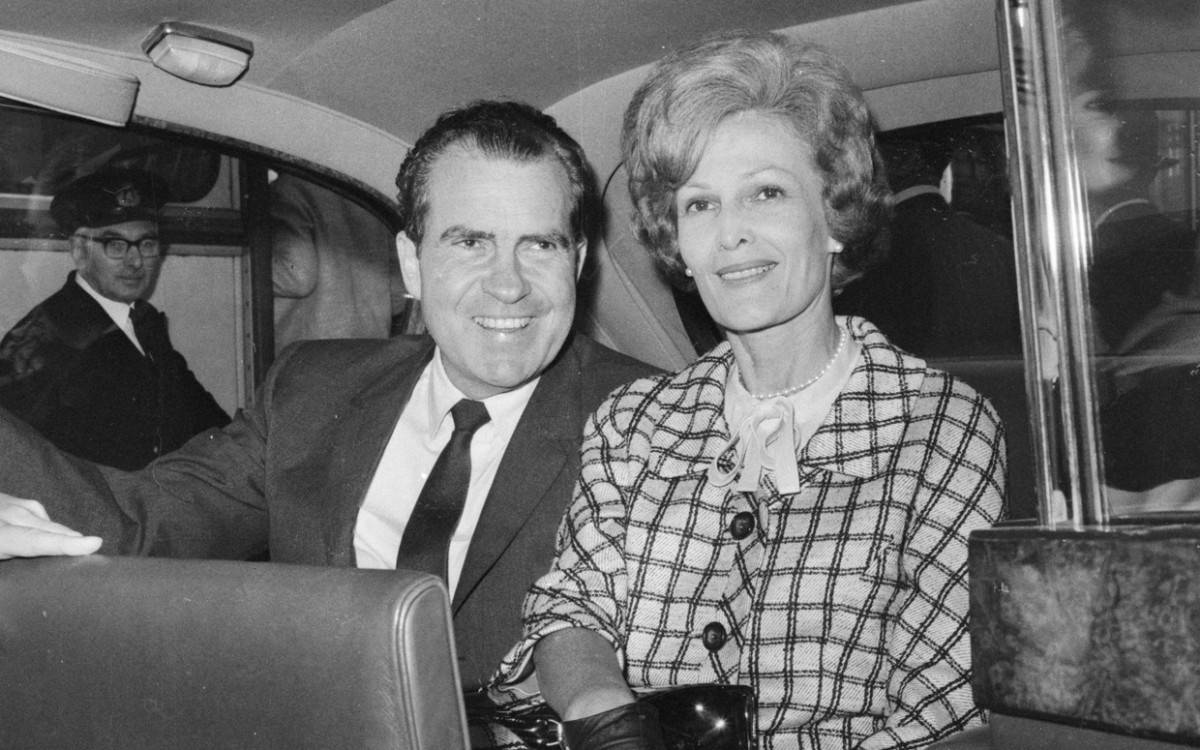

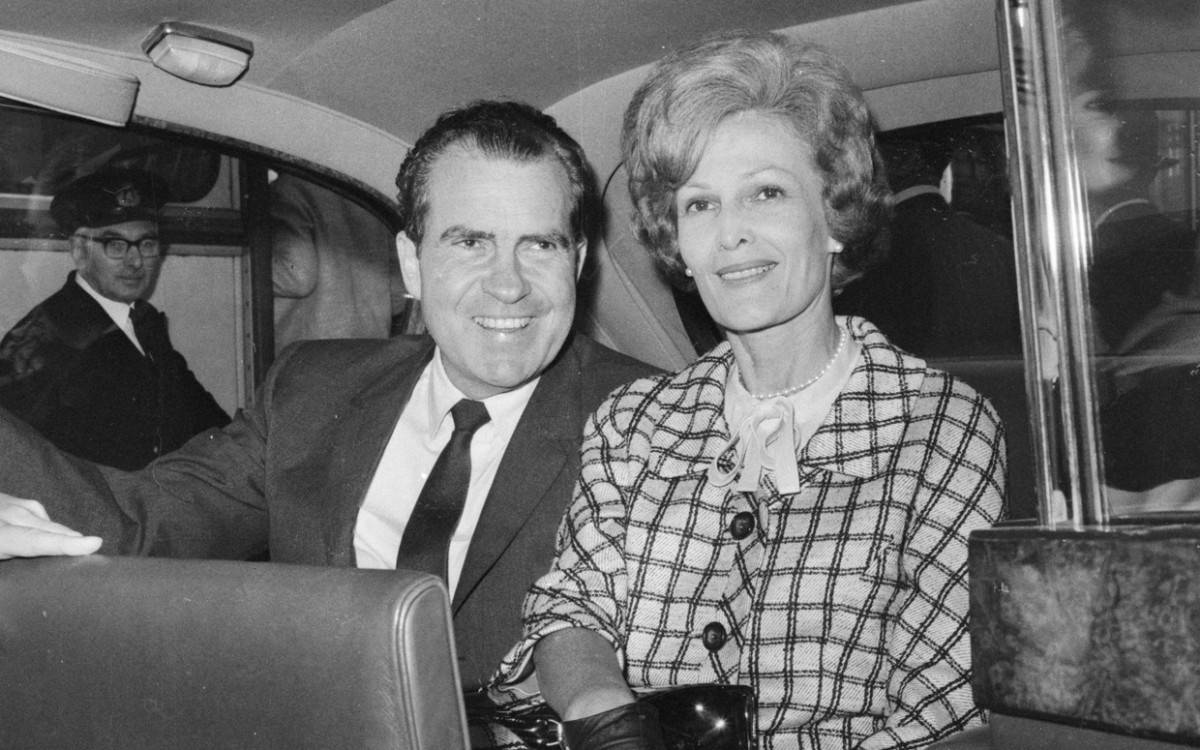

His main regret is the stories he never reported, such as Richard Nixon's 1974 assault on his wife, Pat, before the Watergate scandal forced Nixon to resign from the presidency. According to Hersh, it wasn't the first time. Hersh obtained direct information from the hospital where Pat Nixon was treated, but at the time, he believed the president's personal behavior did not affect his public service. He refers to an 11-year-old girl, often referred to as the "CNN girl" by online supporters of Assad. The heavily cropped photos indeed show the same girl covered in dust being carried by three different men.

This is evidence, it seems, that the girl is an actor, used in staged videos and photos by rebels to show the cruelty of Assad's bombing campaign.

And once again, Seymour Hersh's writing has sparked controversy. Serious allegations that the CIA and the American government were behind the bombing of three out of four underwater Nord Stream pipes in Denmark last September. A rain of denials followed, including attempts to discredit Hersh.

But, as usual, Hers has a final word: "I will wait." Only time can prove whether his writings are true. Just like the massacre at My Lai in Vietnam, the Watergate scandal, and the torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq.

Yes, only time can prove the truth of his writings. As he wrote in his memoir, "Reporter: A Memoir" (2018): "I will happily let history judge my work." (eha)

Source: El Pais, New York Times, Prospect Hersh always regrets his mistakes.

(US President Richard Nixon and his wife Pat Nixon/Parade)

Hersh is not the only famous journalist who has seen his reputation tarnished. Consider the challenges to the honesty of Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuściński as a reporter, British journalist Robert Fisk admitting bias towards the Syrian government, or the personal relationship of Italian reporter Oriana Fallaci with a Lebanese warlord when reporting on the country's civil conflict.

But all these reporters have passed away, and only a few representatives from the golden age of American journalism are still alive – Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of Watergate fame, and Hersh himself.

They are the historians of official and unofficial history and untold stories. They are the last remnants of a profession increasingly torn apart by the struggle between critics and apologists.

***

Seymour Hersh's first major news story — before the revelation of the American massacre in the village of My Lai in Vietnam— was about the US government's secret program to develop chemical and biological weapons.

Concluding that the people most likely to talk to him had retired, he reread army newspaper publications, searching for short stories about retirement parties that often mentioned where the generals retired.

(My Lai Massacre by US soldiers/VFD)

“I got a list of names and addresses, made some phone calls, and went, as eagerly as ever,” Hersh recalled in his memoir, Reporter.

He spent two months on the road, visiting retirees and compiling incredible stories. What he found was undeniable. There were documents, evidence, and the identities of recorded individuals.

Hersh worked for the Associated Press and submitted a 15,000-word story divided into five parts, hoping to make a splash. An editor put it in a drawer. Eventually, over 1,000 words were published, complete with a rewritten introduction claiming that the Soviet program was just as bad. Unfazed, Hersh found another way out, and over time, despite Pentagon denials, the news was accepted and the news was true.

This pattern — getting leads from a source, then digging deeper to find the evidence before struggling to find established media willing to print the story— is one that followed Hersh throughout his career.

(My Lai book written by Hersh/Amazon)

It has made him one of America's best investigative journalists, a reporter whose work must be read, whether it's about the Watergate scandal that led to Richard Nixon's impeachment or the revelation of US torture in the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq.

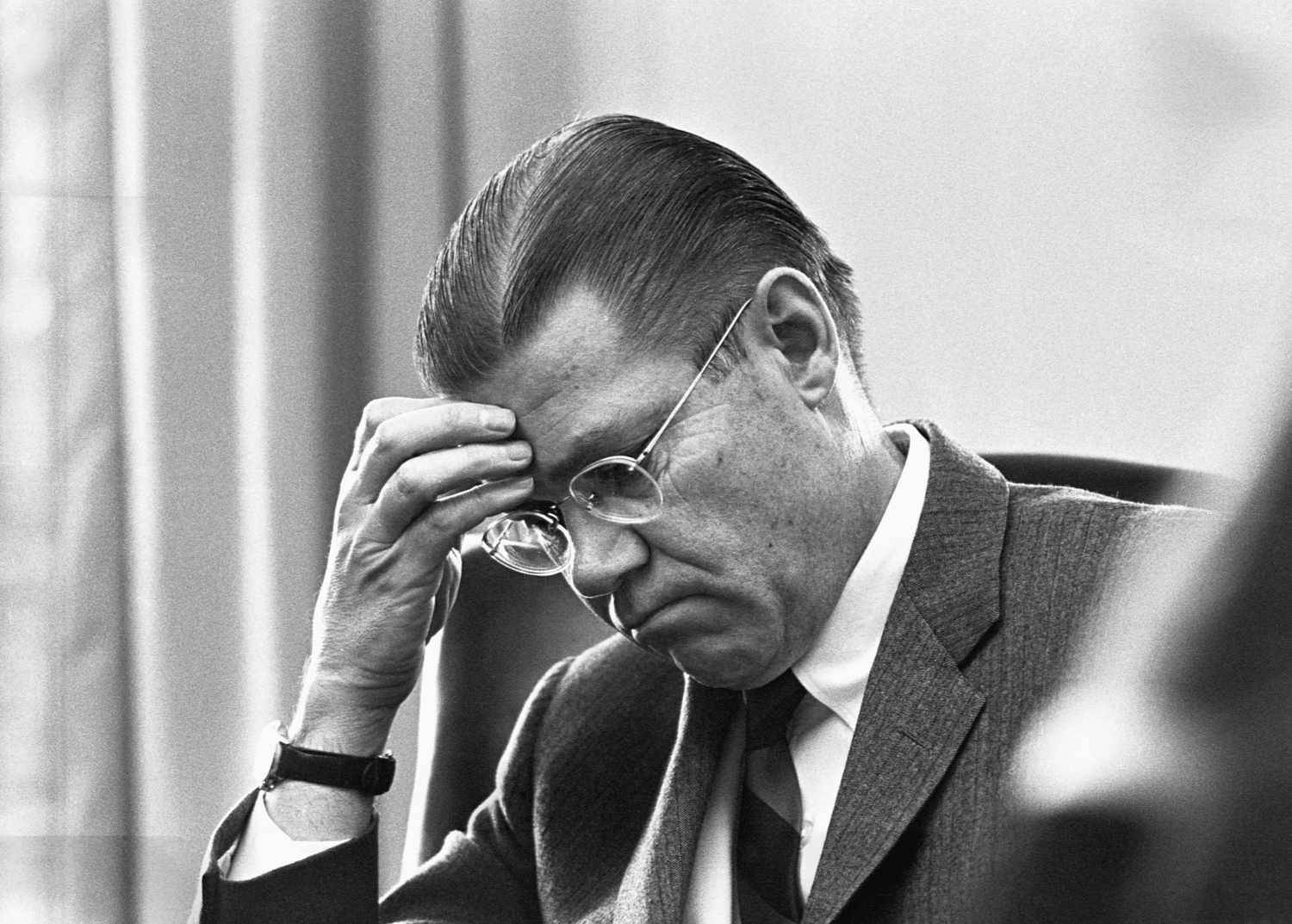

But for the man himself, there is another lesson, perhaps more important: that the US government lies. Robert McNamara, US Secretary of Defense during the early stages of the Vietnam War, was a “psychotic liar,” Hersh said to Prospect when they met in London in June 2018. Henry Kissinger was another “big liar of our time.”

(Robert McNamara, US Secretary of Defense at the beginning of the Vietnam War/ToughtCo)

There were few senior US officials whom Hersh did not distrust, often with good reason. In his book “Reporter,” he accused several presidents, secretaries of state, and various other politicians, from Richard Nixon to Barack Obama, of frequent lying.

And if the US government lied, it meant their opponents might be telling the truth.

“We were always told 'if the Russians say it, it can't be true,' 'if the North Vietnamese say it, it can't be true,'” Hersh said.

"I really learned not to believe that," he said.

***

In 2003, in the early weeks of the Iraq War, Hersh made his first visit to Syria.

In Damascus, he met Bashar al-Assad, the first of several face-to-face interviews he would conduct with the Syrian president over the next five years.

In the book “Reporter,” Hersh's description of Assad is neutral. Assad is described as "tall, thin." Before giving his first answer to Hersh, Assad asked “shyly, if it's okay if he gives me a detailed answer,” as Assad had been told his answers were too long.

(Syrian President Bashar al-Assad/Sputnik News)

Three times, Hersh happily described Assad as "secular," as the Syrian president reiterated his support for America's war against al-Qaeda and the support he provided to the CIA. “Assad's intelligence is crucial,” Hersh claimed.

Assad told Hersh about the "clumsy effort" by the CIA to recruit Syrian intelligence sources within al-Qaeda, which led the source to sever all contacts. Assad “urged” Hersh not to write about it because “he hoped the Bush administration would realize that Syria, a secular country, could be an asset in the War on Terror.”

During this period, Hersh also met with Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Hezbollah, a man he described as "professional and friendly" with a "wry sense of humor." American presidents, Hersh said, “made a big mistake by not dealing with both men,” although he acknowledged that his editor at The New Yorker, David Remnick, “was far more skeptical than I was about Assad and Nasrallah's integrity.”

(Hassan Nasrallah/Khamenei.ir)

Written seven years after the Syrian war, which claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of civilians, the book “Reporter” does not contain criticism of Assad—not once does Hersh reflect on whether his initial impression of the dictator was naive.

Personally, Hersh goes even further. “I like Assad,” he said. “I think he's grown a lot since I met him. He never did enough for human rights, but he keeps moving.”

Hersh cited the arrival of ATMs and the broadcast of a Turkish soap opera about an unwed mother as evidence. “He's gotten better. He's gotten much more confident every year. You can argue with him a little bit.

That wasn't the experience of those who protested against the Assad regime in the southern city of Deraa on March 2, 2011. A group of boys wrote graffiti in support of the Arab Spring. They were brutally beaten by Assad's security forces, triggering brutally suppressed protests by the regime—thus beginning the uprising in Syria.

"No," said Hersh. "I have a different view on the uprising. I haven't written about it yet, but I have a very different view on the war. It goes against what others think."

Hersh's version sounds very similar to Assad's version. The Syrian leader has always claimed that "terrorists" were behind the original protests—sometimes claiming it was al-Qaeda, other times suggesting the involvement of the Israeli secret service, Mossad, and the CIA. Hersh wouldn't say who he believed was responsible for the demonstrations, only that "snipers" killed some of Assad's security forces. "It was a provocation."

***

Hersh's decades-long relationship with The New Yorker ended in 2012, when Remnick rejected an article about Osama bin Laden's death that contradicted the official government line. Instead, Hersh turned to the London Review of Books, where he focused on Syria. Between 2013 and 2015, he wrote three lengthy articles that criticized the most famous atrocities committed in the war: the chemical weapons attacks carried out by the Syrian government.

In one essay, Hersh claimed that the US government knew that the jihadist opposition group, Jabhat al-Nusra, also had sarin gas, but downplayed this fact to justify the bombing campaign against the Assad regime. In another, he claimed that the sarin gas attack was staged by Turkey, in collaboration with Jabhat al-Nusra, hoping to blame it on the Syrian government. If true, these claims would be shocking. The fact that the US government has a different view means nothing to Hersh—remember, they lie.

He also doesn't seem to mind that the formal investigation by the United Nations, although prohibited from assigning blame, made it clear that only the Syrian government could be responsible. ("If you think the UN is an objective place, I have a bridge I want to sell you," Hersh told Prospect.)

(Perang di Suriah/Euronews)

He also doesn't care that human rights groups like Human Rights Watch disagree with him ("Human Rights Watch does some great things. I think the things they do in Syria and Russia are crazy."). He also can't be swayed by widely respected independent analysts like Dan Kaszeta and Eliot Higgins (Higgins is a "couch potato").

But, surprisingly, if he seems to enjoy the disagreement of experts and Western governments, he doesn't mind at all that his work is widely praised by supporters of the Russian and Syrian regimes ("I think they should, why not? They (Syria) deny it and Russia denies it").

Unlike his investigation into America's chemical and biological warfare program in the 1960s, there are no witnesses, no documents, and no damning evidence. Instead, he gets quotes from a handful of unnamed former US officials. For Hersh's supporters, this doesn't matter. It's Sy Hersh, the man who exposed My Lai and won a Pulitzer. That's definitely true.

For the London Review of Books or LRB, Hersh's story becomes problematic. "Mary-Kay Wilmers (LRB's longtime editor) was very nervous about my latest story. She told me she didn't want to be accused of being too pro-Russia and too pro-Syria. Clearly, they think I'm too pro-Syria, a lot of people do."

Wilmers was right to be nervous. The story she published, which appeared in the German newspaper Die Welt, is the most controversial. In it, Hersh states that the recent chemical weapons attack in Khan Sheikhoun was not, as claimed by the UN and the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), a sarin gas attack carried out by the Syrian government. Instead, it was a conventional bomb attack that happened to hit a warehouse containing "fertilizer, disinfectant, and other items." This caused an "effect similar to sarin gas."

Chemical weapons experts say this is impossible. Laboratory tests prove that sarin was indeed used. Hersh disagrees. "Why am I doing this?" he asked at one point. "I don't want to explain this," he said later.

(Seymour Hersh muda saat menjadi wartawan New York Times/NYT)

Hersh likes to portray himself as a principled reporter who bucks the mainstream. It doesn't matter if others don't believe him. "I'll wait," he said.

But is this true? While many of his stories have been slammed by the US government, they are too persuasive to ignore, and have been followed up by other media outlets. His My Lai coverage crossed the Atlantic and appeared on the front pages of the New York Times. His Watergate story was followed up by the Washington Post. His Abu Ghraib exposé aired on US television. It has become accepted truth—because it's entirely true.

Today, his latest work leads the headlines on RT, the Kremlin-funded news channel that harshly echoes the Russian government's line on Syria (and, indeed, everything else). It is enthusiastically shared on social media by pro-Assad supporters.

In his defense, Hersh likes to quote the work of Ted Postol, a professor of science, technology, and national security policy at MIT. Postol has appeared on a podcast run by a Holocaust denier, where he talked about how he relied on his work in Syria on a pro-Assad blogger, Maram Susli, who uses the name Syrian Girl.

Hersh is angry. "He talked to her about one thing," he said, waving his hand in frustration. "Oh my God, he talked to her once." Postol's work is often discussed on Infowars, a conspiracy theory channel run by Alex Jones—who has claimed that the Sandy Hook school massacre, in which 20 children under the age of eight were killed, was a hoax.

"What's Infowars?" Hersh asked. Run by Alex Jones. "Oh, he's crazy. Alex Jones is crazy. I can't be responsible for what he runs."

***

Most of the criticism of Hersh relies on the idea that something has changed, that the legendary investigative journalist of the 1960s and 1970s has become a conspiracy theorist who doesn't care about facts.

Others whisper unkindly about old age. A friend who has written about Syria for over a decade called Hersh's recent work a "senile deviation."

Hersh would deny it, loudly. "I have the same sources. I haven't changed. I have people who see a lot of things." They talk to me... What can I say? I only operate at a different level."

There is something else that hasn't changed— their strong belief that the American government lies. They lied about chemical and biological warfare programs. They lied about Vietnam. They lied about Abu Ghraib. And now, of course, they are lying about Syria.

(Book by Seymour Hersh, "Reporter/JUF)

But after decades of exposing the lies of the American government, it seems as if he has forgotten that other governments have their own reasons to lie.

And when it comes to regimes appointed by America— like Syria— Hersh's skepticism, curiosity, and "why-do-bastards-always-lie-to-me?" approach are completely absent.

Hersh doesn't see it that way. "If you think I'm going to throw away my 45-year reputation for Bashar al-Assad." He let out a loud, joyless laugh.

***

The conversation between Prospect and Hersh ended late at night, but Hersh had one more promise: an interview with RT. This special 30-minute interview, with only Hersh and the interviewer, whose line of questioning is on the more pleasant end of the spectrum.

In the midst of explaining his report, Hersh tries to downplay his criticism by claiming they are part of a "propaganda organization."

"Too often we see the same child in photos from year to year, always covered in dust," he said.

Disclaimer: This translation from Bahasa Indonesia to English has been generated by Artificial Intelligence.