The Collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, 10 Days that Shook the Market

It is a top bank that is 40 years old.

Dream – March 2023 is an optimistic month for Jonathan Nelson, 50 years old.

Jonathan Nelson has committed $2 million or IDR 30 billion in new funding for his financial technology startup company, HF.Capital, from two investors last month. He targeted $2.5 million and thought he would secure the rest in a "careless" manner.

Then suddenly, 67 investors rejected his proposal. In mid-March, the two initial investors also withdrew. Nelson was initially puzzled by the cold attitude of the investors. But two days later, when Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), the leading bank for startups and venture capital companies, collapsed after technology and startup investors made massive withdrawals or a bank run, everything made sense.

(Jonathan Nelson, founder of HF.Capital/Forbes)

"I scratched my head, saying, 'Why are they acting like they're seeing ghosts?'" he said. "Then a bank run happened, and I was like, 'Ah, apparently they're scared.'”

After a terrible 2022, when money dried up for startups, causing valuation declines, reduced ambitions, and widespread layoffs, many hoped things would pick up again in 2023. But the collapse of SVB has triggered more anxiety and fear, which is starting to materialize in new deals throughout Silicon Valley.

Late Sunday night, the collapsed SVB was finally acquired by First Citizens BancShares. The former parent company of the failed bank, SVB Financial, filed for bankruptcy on March 17 and plans to run a separate process to sell various units.

(The collapsed SVB was finally acquired by First Citizens BancShares/Fox Business)

During the past two weeks, while regulators rushed to find a buyer for SVB, the companies that relied on it for credit lines rushed to secure new sources of debt. Investors, wary of risks, increasingly chose to sit on the sidelines or were too busy helping support existing startups to pursue new deals. And some new startup companies did what they could to avoid raising new funds so they wouldn't have to face lower valuations, heavy requirements, and rigorous due diligence.

The result is that the environment for technology startups quickly became colder.

"People realized it might not get better," said Mathias Schilling, an investor in venture capital firm Headline. "It was a big surprise to the system."

He said the bank run that caused SVB's demise showed how much fear already existed in the market. Investors wouldn't trigger panic like that if they weren't ready.

The collapse of SVB was not directly caused by a technology downturn, and new companies pivoting there won't lose their deposits because the Department of the Treasury and the Federal Reserve eventually guarantee all customer deposits at SVB. But the institutional explosion occurred on top of a 61% decline in venture funding over the past three months of 2022 from the previous year, according to PitchBook, which tracks startup funding. Kyle Stanford, a PitchBook analyst, said he expected the collapse of SVB to "accelerate" the ongoing venture funding decline.

“We've been experiencing a slowdown in business for a year now,” he said. “This is just an additional problem the market doesn't need.”

In a survey of 870 founders conducted last week by venture capital firm NFX, 59% said the collapse of SVB would make the already difficult fundraising market even harder. Twenty-two percent said they worried they wouldn't be able to raise any funds this year.

Techstars, a startup investment firm that has supported 3,500 new companies, advised its companies to ask their shareholders for more money before approaching new investors, said Maëlle Gavet, the company's CEO. Techstars has also tried to lower entrepreneurs' expectations about the size of their company's valuation, urging them not to see lowering their valuation as a failure but as a positive sign that someone is willing to invest in their company.

(Maëlle Gavet, CEO Techstar/Business Journals)

Gavet said she expected many conversations to take place this summer about whether new companies should be shut down or sold. “The whole SVB thing created a high sense of danger,” she said.

Bijan Salehizadeh, an investor who owns stakes in a dozen venture capital funds, said a third of the companies he backed would run out of money in the next six months. He called this the "worst time in recent memory to raise new venture funding" and added that he had seen many investors "sitting on the sidelines" recently because they were very nervous.

Ayham Ereksousi plans to raise $4 million or IDR 60 billion for his startup company, Stomio, which offers software to help companies test new products with their customers. But he has lowered his expectations. He has been in contact with between six and eight investors who expressed interest in investing late last year. But in recent weeks, when he tried to raise money, many did not respond or said they had changed their investment strategy.

Now Ereksousi is considering raising less money from existing investors and coming back next year for a larger fundraising. This year is likely to be "useless," he said, and concerns about the health of the bank are "casting a shadow over the entire funding ecosystem."

If startups cannot raise venture funding, there are few other lifelines available. Stock market volatility has made initial public offerings nearly impossible, while large technology companies are under antitrust scrutiny and facing their own financial pressures.

SVB offers many startups a form of credit that other banks consider too risky because new companies are generally not profitable. That debt, typically secured by startup venture funding, helps companies stretch their money into the next funding round.

Nelson, the founder of HF.Capital, was previously a venture capitalist and had a portfolio of 75 investments. Before SVB collapsed, he informed those companies that funding might start flowing again in the spring.

(Jonathan Nelson's startup HF Capital/CRaiflist)

Now he recommends they wait until September to raise money. Those in desperate need of cash may have to think of ways to become profitable.

That's the plan for HF.Capital. Nelson wants to use $2.5 million to secure regulatory licensing for software products that enable international stock trading. But with investors pulling out, he now plans to grow it using his own profits rather than outside funds.

"That's just a brick wall," he said. "No one is writing checks now," he said, as quoted by the New York Times.

***

On March 10, 2023, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) collapsed after experiencing a massive customer fund withdrawal or bank run, marking the second-largest bank failure in US history and the largest since the 2007–2008 financial crisis.

Seeking higher investment returns, in 2021 SVB began shifting its securities portfolio from short-term Treasury bonds to long-term ones.

The market value of these bonds has declined significantly during 2022 and into 2023 as the Federal Reserve raised interest rates to curb inflation spikes, resulting in unrealized portfolio losses.

![]()

(Silicon Valley Bank office closed after a "bank run"/CNN)

Higher interest rates also raised borrowing costs throughout the economy, and some Silicon Valley Bank clients began withdrawing money to meet their liquidity needs.

To raise cash to pay for these withdrawals, SVB announced on Wednesday, March 8, 2023, that they had sold securities worth more than $21 billion, borrowed $15 billion, and would hold an emergency sale of some of their shares to raise $2.25 billion.

This announcement, coupled with warnings from prominent Silicon Valley investors, caused the bank to collapse as customers withdrew $42 billion the following day.

On the morning of March 10, 2023, the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation seized SVB and placed it under the curatorship of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

Approximately 89 percent of the bank's $172 billion in deposit liabilities exceeded the maximum amount insured by the FDIC. Two days after the failure, the FDIC received extraordinary authority from the Department of the Treasury and announced, along with other institutions, that all depositors would have full access to their funds the following morning.

Seeking to auction off all or part of the bank, the FDIC reopened it on March 13 as a newly formed bridge bank, Silicon Valley Bridge Bank, N.A.

Although some considered the government's response a bailout, the plan did not require a rescue of the bank, its management, or its shareholders, but rather made uninsured depositors whole from the proceeds of the bank's asset sales, without using taxpayer money.

The collapse of SVB had significant consequences for startup companies in the US and abroad, with many startups unable to withdraw money from the bank. Other major technology companies, media companies, and wineries were also affected. For a number of their founders and venture capital backers, this was the bank of choice.

In its history, SVB was a commercial bank founded in 1983 and headquartered in Santa Clara, California. At its collapse, SVB was the 16th largest bank in the US and heavily inclined towards serving technology industry companies and individuals.

Nearly half of US venture capital-backed healthcare and technology companies were financed by SVB. Companies like Airbnb, Cisco, Fitbit, Pinterest, and Block, Inc. were clients of the bank.

![]()

(Airbnb is one of Silicon Valley Bank's customers/CityReality)

In addition to financing venture-backed companies, SVB was known as a source of private banking, personal credit lines, and mortgages for tech entrepreneurs, specializing in lending money to riskier new companies.

Until March 9, 2023, SVB was in "sound financial condition," according to the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation, despite an increasing number of short sellers targeting SVB at the beginning of the year. Employees received their annual bonuses on March 10, 2023, a few hours before the government took over the company.

In the bank's latest call report, filed on December 31, 2022, the bank had total assets of $209 billion, with total deposits of $175.5 billion, of which the bank estimated $151.6 billion (86.4 percent) were uninsured.

![]()

(Cisco is one of Silicon Valley Bank's customers/New York Times)

The bank's deposits increased from $62 billion in March 2020 to $124 billion in March 2021, benefiting from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on science and technology. Most of these deposits were invested in long-term Treasury bonds as the bank sought higher investment returns than those available on short-term bonds.

The market value of these long-term bonds has declined as interest rates have risen during the 2021–2023 inflation spike and become less attractive as investments compared to newer bond issuances. In April 2022, SVB's chief risk officer resigned, and his replacement was not mentioned until January 2023—a period coinciding with the period of rising interest rates.

By the end of 2022, the bank had a bond portfolio worth $117 billion, divided into a held-to-maturity portfolio worth $91.3 billion and an available-for-sale portfolio worth $26 billion. At that time, unrealized losses to market on the securities held to maturity exceeded $15 billion.

![]()

(Pinterest is one of Silicon Valley Bank's customers/NP)

SVB did not hedge against interest rate risk on a portion of its bond portfolio, seemingly for the same reasons as most banks: hedging itself would rebound with the market, whereas the purpose of holding bonds to maturity is to hold them to maturity.

At the same time, startups began withdrawing deposits from the bank to fund their operations as private financing became increasingly difficult to obtain. A series of layoffs in the technology sector starting in 2022 also led depositors to withdraw their deposits.

During the first half of 2022, the bank realized a profit of $517 million by unwinding $11 billion of interest rate swaps on the available-for-sale bond portfolio.

By the end of 2022, there were only $563 million in swaps protecting that portfolio. In early 2023, to raise the necessary cash to fund the withdrawals, the bank sold all available-for-sale securities, realizing an estimated $1.8 billion loss.

In early 2023, the Federal Reserve put SVB under "horizontal review" for its risk management procedures.

A week before the collapse, Moody's Investors Service reportedly informed SVB Financial, the bank's parent company, that they faced a potential double downgrade due to unrealized losses.

On March 8, 2023, SVB announced it had sold investments worth more than $21 billion, borrowed $15 billion, and would hold an emergency sale of its shares to raise $2.25 billion, including $500 million to General Atlantic. JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America declined the opportunity to acquire the bank. Despite the bank's actions, Moody's downgraded SVB on March 8.

Investors in several venture capital firms, including executives at Founders Fund owned by Peter Thiel, Union Square Ventures, and Coatue Management, urged their portfolio companies to withdraw their deposits from SVB, with Founders Fund withdrawing all of its funds from the bank on the morning of March 9.

(Peter Thiel, founder of Founders Fund, called for withdrawals from SVB causing a "bank run"/Guardian)

By the close of business that day, customers had withdrawn $42 billion, leaving the bank with a negative cash balance of approximately $958 million. Among the financial service companies that received money from SVB customers are Brex, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, and First Republic Bank. The value of SVB stocks plummeted until trading was finally halted on the morning of March 10.

On the morning of March 10, examiners from the Federal Reserve and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) arrived at SVB's office to assess the company's finances.

A few hours later, the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation issued an order to take over SVB, citing inadequate liquidity and bankruptcy, and appointed FDIC as the receiver.

The failure of SVB is the largest bank failure based on any bank's assets since the 2007–2008 financial crisis and the second-largest failure of a bank insured by FDIC.

Silicon Valley Bank was shattered.

***

As a result of SVB's collapse, bank stocks worldwide have plummeted in the past few days due to concerns that the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) could trigger a broader crisis in the sector.

The speed at which market anxiety spread worldwide has forced bank executives and regulators to move at an unprecedented pace: US authorities guaranteed all deposits in SVB and the smaller Signature Bank 48 hours after the collapse. Just a few hours later, Credit Suisse's stock price plummeted on Wednesday, and the Swiss central bank stepped in with a $54 billion loan.

Although there is nothing new about the financial emergency, this crisis—and the response it generated—is unique because it was accelerated by the buzz on social media platform Twitter, which triggered panic.

Bank run occurs when customers lose confidence in an institution's ability to safeguard their money, and a large number of them withdraw their deposits all at once. The more people withdraw their funds, the more likely the bank will face serious difficulties, causing more customers to flock and demand their money back.

![]()

(Customers try to withdraw their savings from Silicon Valley Bank even before the bank opens/Guardian)

The collapse of SVB is the second-largest bank failure in US history. The largest, Washington Mutual Inc, in 2008, lasted for eight months. The collapse of SVB lasted only two days.

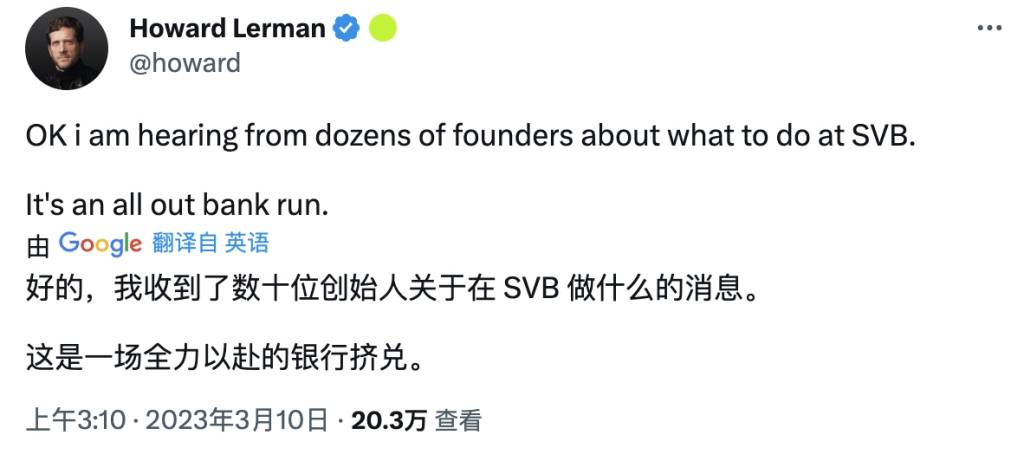

Twitter posts and messaging exchanges on WhatsApp that caused concern, coupled with the ease of access provided by online banking, are seen by analysts as serious catalysts for the current banking crisis.

Experts suggest that in the era of social media, the psychological behavior behind a bank run—mass fear of depositors losing their savings—can be reinforced and go viral faster than can be effectively responded to by bank officials and regulators.

Michael Imerman, a professor at the Paul Merage School of Business at the University of California-Irvine, said that what happened at SVB was a "bank sprint, not a bank run, and social media played a central role in that."

What some SVB customers realized a week ago is how vulnerable their bank was. Like all banks, it had invested its customers' deposits, with most of its money going into long-term US government bonds.

The problem is that bonds have an inverse relationship with interest rates, so when the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates rapidly to combat inflation, the bonds held by SVB started losing significant value.

Many SVB customers were also hurt by rising interest rates and needed to access their deposits to meet daily business expenses. But with their investments trapped, the bank struggled to meet their customers' demands.

The decision to raise funds through stock sales proved to be the bank's death knell. Venture Capital firm Founders Fund, owned by Peter Thiel, reportedly instructed companies in its portfolio to move their money from SVB.

In the gossip-filled world of Silicon Valley, this news spread like wildfire. Customers withdrew $42 billion—one-fifth of SVB's deposits—within just a few hours.

Mark Tluszcz, CEO of Mangrove Capital, tweeted: "If you didn't advise your company to withdraw cash, then you didn't do your job as a board member or as a shareholder."

(One of the tweets that triggered a "bank run" in SVB/Twitter)

Investor Bill Ackman tweeted that if federal regulators did not step in quickly and guarantee all deposits, a run on other banks would begin on Monday.

“You should be genuinely scared right now,” tweeted investor Jason Calacanis, using all capital letters for emphasis. “That's the appropriate reaction to a bank run and contagion.”

Other prominent entrepreneurs also sounded the alarm, spreading their messages on social media, resonating strongly with bank customers who tend to be tech-savvy entrepreneurs interested in online discussions.

Congressman Patrick McHenry, Chairman of the US House Financial Services Committee, referred to the turmoil as the "first Twitter-induced bank run."

Some messages that caused cold sweats among financial customers turned out to be misleading, prompting calls to focus on facts rather than speculation.

(Twitter posts that triggered a "bank run" in SVB/Wall Street Journal)

“The past few days have been a unique incident triggered by misinformation on social media and do not reflect the health of our industry,” said Lindsey Johnson, President of the Consumer Bankers Association, in a statement.

SVB may be the first bank to be run in the social media era, but it is not the first bank to have its fundamental business shaken by rampant Twitter speculation.

On Thursday morning, Swiss bank Credit Suisse announced it would take a $53.7 billion loan from the Swiss central bank to support its finances after its stock price fell by as much as 30%. The sell-off occurred when the bank's largest shareholder, Saudi National Bank (SNB), ruled out providing fresh funds due to restrictions limiting its ownership.

However, the chairman of SNB said Credit Suisse is a "very strong bank" and seemed to not need more cash after a massive restructuring plan last fall. The limitation on how much stock it could own was the reason for not investing further.

Credit Suisse's problems are not new; the bank has gone through a series of scandals and stock fluctuations over the past decade, leading to client exodus, cash withdrawals, and contributing to losses that grew to 7.3 billion Swiss francs in 2022.

(Bank Credit Suisse's stock also plummeted due to tweets/Mint)

But last October, its stock fell by 12% in one day after a journalist tweeted that a "major international investment bank" was on the brink. The tweet was later misquoted by investment.com, which tweeted it to their thousands of followers. The rumor spread like wildfire on online forums and social media accounts, but at least it was unfounded.

Credit Suisse's problems were already well-established at that time, and its stock price had been declining for months, but experts pointed to the tweet and subsequent spread as highly damaging to the bank.

Regulators, policymakers, and bankers are now, according to the Guardian, forced to look at the role that social media may play in the current upheaval—and figure out what they can do to stay ahead of rumors.

As a result, the combination of investments in long-term bonds that declined in value as the Fed raised interest rates to control inflation, and issues on Twitter containing calls from investors to withdraw massive amounts of funds from Silicon Valley Bank, was a perfect combination to kill SVB. In just one day, there was a massive withdrawal of funds from customers amounting to U$ 42 billion or Rp 634 trillion. No wonder, no matter how big a bank is, it will collapse. This is the risk of banks in the era of social media. And startups can only groan. (eha)

Source: The New York Times, CNN Business, Financial Times, Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, BBC, Guardian,

Cobain For You Page (FYP) Yang kamu suka ada di sini,

lihat isinya

It is a top bank that is 40 years old.

Even in the month of Ramadan, we still need to seek His protection, because we do not know what dangers will befall us from the evil intentions of humans.

The government officially provides tax incentives for electric cars and electric buses from April to December 2023.

The following examples of bismillah calligraphy can be easily imitated by you.

Already worn for a year, this woman asks to exchange clothes with a new one at the cashier of the store.

Dito Ariotedjo was inaugurated by President Jokowi together with the head of BPNT.

With his hands handcuffed, Rafael was seen escorted by security officers and KPK investigators to the press conference room.

The Central Statistics Agency (BPS) said that food commodity prices will start to rise ahead of Idul Fitri or Lebaran 2023.

Ernie Mieke admitted that at that time she wanted to apologize directly and meet the victim.

This is how to stay productive while fasting in Ramadan.

This action, when not taken care of properly, will become a difficulty for someone to find their soul mate.

Wives who are cheated on, their deeds and rewards belong to the wife.